But that is all beside the point at the moment (and a tad distracting), so without further ado here are my latest readings & ratings:

1. The Dovekeepers (2011) by Alice Hoffman

Applicability Rating: 8/10

Relevant Themes: Interplay of masculine/feminine traits – ‘doing’

gender, challenging gender roles, leadership in crisis, relationships between

women, divine feminine (celebration of the feminine)

Key Thoughts: Love, love, love this book! Although, since I read it over Christmas, it almost

ruined my tenuous grasp on the ‘spirit of Christmas joy.’ The story was incredibly sad and, as it is based on true events, disturbingly

tragic (I shed more than a few tears near the end).

Set in 70 AD just after the fall of Jerusalem, The Dovekeepers retells the tragic story of Masada, a small Jewish stronghold

on a mountain outside the Judean desert. Nine hundred Jews held out for several

months against the Romans, but by the end of the siege, only two women and five

children had survived. The tale is told from the perspective of four

extraordinary women whose lives become inextricably intertwined when they

become dovekeepers at Masada – Yael, the unwanted daughter of an assassin,

Revka, a baker’s wife who has witnessed unspeakable brutality, Aziza, the

daughter of a warrior, and Shirah, a wise and powerful woman who some suspect is a

witch.

Not only is the story compelling, but the novel also explores the leader-follower relationship from the position of the female follower. Yael is particularly observant of the charismatic appeal found in the ‘leader’ figure: “No one wanted to think about Masada without a leader, a body without a spirit” (p. 98), yet she is also somewhat critical of the godlike and masculine appeal of Ben Ya’ir, a man who “shone because others followed, because they adored him and deferred to him and trusted him…there was a light inside him,” and why they followed him “to this remote and dangerous place” (p. 99).

In Aziza’s section, Hoffman investigates the tensions

between traditional gender binaries and what happens/doesn't happen when they are transgressed.

Aziza has lived an unconventional life; although born female, to help her

survive in the harsh desert as part of a mountain Moabite tribe, her mother

brings her up as a boy. But before she arrives at Masada she reverts back to

her female ‘identity.’ However, as the Romans begin their siege, Aziza once

again transforms herself into a ‘man.’ Compared to her sister Nahara who joins

the Essene people and lives “as if she was nothing more than a passive and

beautiful ewe” (p. 284), Aziza is a force to be reckoned with. The gender interplay

alone provides plenty of material for discussion about the ‘nature’ of masculine

and feminine traits, and the ways in which masculinity and femininity are perceived and the expectations they create.

I loved the sense of 'humanity' in this novel and the way it celebrated

the feminine. By allowing some characters to move beyond gender

boundaries and enact and play with both the masculine and the feminine, the agentic and the

communal, Hoffman has created a story which transcends time boundaries.

2. Flow Down Like Silver: Hypatia of Alexandria, a novel (2009) by Ki Longfellow

Applicability Rating: 7/10

Relevant Themes: Female leadership in male-dominated

societies, women’s achievements, perceptions & expectations

Key Thoughts: “Hypatia? Who is she?” I felt I should know, so by the end of the first chapter I was desperately wracking my brain searching for a reference point, some long ago cataloged fact. “Nothing…wait, a

movie…Yes! Got it, Agora.”

It’s rather disappointing when all you can remember about

such a remarkable woman is that she was killed by a Christian mob sometime in

400 AD, and this from a rather poorly executed movie (as my hubby would claim –

the best form of historical (mis)information). Longfellow no doubt thought it was

disappointing too, which is why she wrote Flow

Down Like Silver, a novel which celebrates Hypatia’s sublime genius in a

time period when it was almost completely and exclusively a ‘man’s world.’ Not only was Hypatia of Alexandria a leading Greek

mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher in the 5th century, she

was also head of the Neoplatonic school at Alexandria where she taught

philosophy and astronomy to men – ‘pagans,’ Christians, and Jews alike – during

a time of political and cultural upheaval.

I thoroughly enjoyed this novel and the depth with which Longfellow explores Hypatia’s philosophical inclinations (she even has

Hypatia debating with Augustine) and bravery in the face of stringent

opposition from the leading religious powers. There is no doubt Hypatia deserved to work in the public sphere and male-dominated education

system.

However, I feel there could be problems with workability. The narrative switches haphazardly between protagonists. Personally I would have preferred if the story had followed only Hypatia, or at least Hypatia and Minkah. There is a LOT of philosophy/abstract reasoning sprinkled throughout the text, I love that kind of thing, but it could be a bit tiresome for those wanting a quick, easy read (one of the keys I think is having a story or novel which someone could read in one weekend – books like The Lifeboat and The Dovekeepers are much harder to put down due to the compelling nature of their plots. Saying that, Badaracco still includes more challenging reads like Antigone by Sophocles in his selection).

However, I feel there could be problems with workability. The narrative switches haphazardly between protagonists. Personally I would have preferred if the story had followed only Hypatia, or at least Hypatia and Minkah. There is a LOT of philosophy/abstract reasoning sprinkled throughout the text, I love that kind of thing, but it could be a bit tiresome for those wanting a quick, easy read (one of the keys I think is having a story or novel which someone could read in one weekend – books like The Lifeboat and The Dovekeepers are much harder to put down due to the compelling nature of their plots. Saying that, Badaracco still includes more challenging reads like Antigone by Sophocles in his selection).

3. In the Name of Friendship (2005) by Marilyn French

Applicability Rating: 7/10

Relevant Themes: Third-wave Feminism (in constrast to

second-wave), friendship, middleclass women’s careers, changing expectations

Key Thoughts: Written in 2005 and published by The Feminist

Press, In the Name of Friendship is a

sort of pseudo-sequel to The Women’s Room

(originally published in 1977). French obviously realised the need to re-visit

the status of the ‘gentler sex’ and relook at the opportunities for

(predominantly) white women in the West, and I’m glad she did! I found this

novel to be much more relatable (no surprises there!) and in line with the

experiences of my own and my mother’s generation.

Set in a small Berkshire town in Massachusetts, the novel opens

with the formidable, yet kind-hearted seventy-six year old Maddy Gold stating

matter-of-factly: “Things are entirely different for women today.” It is on

this premise which French bases her updated exploration into the ‘truth’ behind women’s

lives (and to a lesser extent, men’s lives) at the turn of the century. The

story brings together four unlikely friends of differing ages and with completely

different life experiences, and it seems that what French is really wanting to

celebrate is the beauty and necessity of multigenerational female friendships.

Although there is not much in the way of plot or action (it

reads quite similarly to other French novels – a type of thoughtful, but

disjointed narrative filled with gems of insight and wisdom; ‘real-life’

in all its mundane, everyday glory), as Stephanie Genty notes in her afterword: for readers who are searching for a feminist messages in novels, In the Name of Friendship offers a clear

one: “at the beginning of the twenty-first century, more than forty years after

the start of the women’s movement, at least privileged women can choose to

experience ‘more life’” (p. 389). So it, of course, focused on “female

experience in the widest and deepest sense: woman in relation to significant

others, in relation to her body and sexuality, in relation to work and creative

experience, and in relation to society as a whole” (p. 391).

Does it examine or say anything interesting

about women’s leadership? Not overtly. However, it does explore the double-bind

women face when it comes to work and family, along with discussing subtle misogyny

and sexism in the workplace (there’s an excellent scene where Alicia’s husband,

with Alicia’s gentle prompting, comes to the realisation that he has biased

perceptions of his female colleagues). As a preliminary text (and by

preliminary I mean the type of novel you’d use to kick off the whole discussion

of gender and work, an ‘awareness raising’ type of text) it could be useful.

4. The

Gracekeepers (2015) by Kirsty Logan

Applicability Rating: 5/10

Relevant Themes: Gender play, feminist science fiction

Key Thoughts:

The story is supposed to follow the lives of two unusual girls,

North and Callanish. They live in a familiar yet mysterious world where the sea

has flooded the earth and living on land is a privilege for only the lucky few. North,

the circus bear girl, and Callanish, the unwanted gracekeeper, both have

secrets which could destroy their lives, and it is because of these secrets that

they are drawn to one another. There is a lot of gender play in this book,

particularly in terms of androgyny, as well as in a critique of organised religion

which is interesting but…there was too much of everything in this short book,

too many themes explored, too many characters trying to find a place in the

narrative, too many random plot details, etc…And since the book is only 280

pages long (the font is larger than normal and the margins are wide), the

ending seemed rushed and forced.

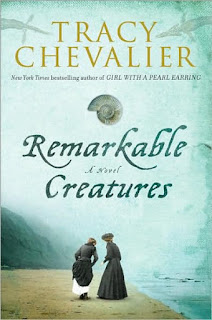

5. Remarkable Creatures (2009) by Tracy Chevalier

Applicability Rating: 7.5/10

Relevant Themes: The ‘space between’ leaders & followers

(moments between Mary Anning and Elizabeth Philpot), psychology of prejudice,

female friendship

Key Thoughts: Remarkable

Creatures retells the true and fascinating story of Mary Anning, a young working

class girl in 19th century Britain with a talent for finding fossils

(or ‘curies’ as the locals call them) along the English coastline. To say the

least, I learnt a lot about fossils – ammonites in particular, but also Mary’s

biggest discovery, a huge ancient marine reptile called an ichthyosaurus. This

discovery, and more like it, shook the scientific community, but Mary was

barely acknowledged for her significant and difficult work (not only finding and dislodging

the delicate fossils from the rock, but also cleaning and piecing the creatures

together).

Mary’s story intersects with that of another fossil hunter,

Miss Elizabeth Philpot, a prickly middle-aged London spinster who has been effectively banished

to the small town of Lyme Regis with her two unmarried sisters. Elizabeth and Mary form an

unlikely friendship which crosses class boundaries, sharing a unique passion (and at

times, rivalry) for finding fossils. Between them they share many ‘moments’ of

leadership as they struggle for recognition in the male-dominated scientific

community. It's a charming novel, but underpinned with a kind of haunting sadness or disappointment over the unfair way Mary is treated - if only she had been given the same opportunities as men, what more she could have been and done. As Elizabeth observes, as the 'outcasts' of society (female, working class, spinsters) they are only allowed one or two small adventures in an otherwise unadventurous life.

6. Almost Famous

Women (2015) by Megan Mayhew Bergman

Applicability Rating: 4/10

Relevant Themes: Women’s lives, real women, missed

opportunities

Key Thoughts: I had really high hopes for this book of short

stories, and while it is very well-written and demonstrates the enviable

versatility of Megan Mayhew Bergman’s writing style, I felt like something (an

‘essence’? depth?) was missing. The purpose of the collection is to give ‘life’

and attention to a set of unlikely heroines who were born in proximity to the spotlight

but, for a variety of reasons, struggled to distinguish themselves or were unjustly

relegated to the footnotes of history. Most of the stories are very sad – about

unfulfilled potential, reckless decisions and, subsequently, loneliness and

bitterness. And while Mayhew Bergman is superb at characterisation, the women

she describes are more atypical anomalies than relatable or inspiring examples.

Lists & Classifications

This table is a basic ‘representation’ of women’s literature that I have

begun ‘grouping’ into themes/categories (it looks a bit messy because it had to fit the dimensions of this humble blog!).

The criteria for selection emerged as follows:

- At least one female protagonist/heroine who guides or is subject to the majority of action in the story

- Written after 1970 by a female author

- Well-reviewed and/or award-winning literature (I've tried to stay away from 'chick lit' as much as possible)

- Interesting/provocative story line

- Universal appeal (suitable for a ‘general’ audience)

- Possible 'leadership' themes

Historical

Literature / Historical Drama:

[Pre-1900]:

·

The Red Tent

by Anita Diamant

·

Year of Wonders by Geraldine Brooks

·

Lavinia by

Ursula Le Guin

·

Flow Down Like Silver: Hypatia of Alexandra by Ki Longfellow

·

Remarkable Creatures by Tracy Chevalier

·

Pope Joan by

Donna Woolfolk Cross

·

The Dovekeepers by Alice Hoffman

[Slavery/American

History]:

·

The Invention of Wings by Sue Monk Kidd

·

The Last Runaway by Tracy Chevalier

·

Property by

Valerie Martin

·

The House Girl by Tara Conklin*

[Pre-1980]:

·

The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver

·

In the Time of Butterflies by Julia Alvarez

·

The Lifeboat by

Charlotte Rogan

·

The Boston Girl by Anita Diamant

·

Day After Night by Anita Diamant (WW2)

·

The Nightingale by Kristin Hannah (WW2)

·

Girl Waits with Gun by Amy Stewart (crime fiction)

·

The Help by

Kathryn Stockett

|

Modern/Contemporary

Fiction (1980 – 2015):

·

The Secret Life of Bees by Sue Monk Kidd

·

How to be Both by Ali Smith

·

Outline by

Rachel Cusk

·

A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley

·

White Oleander by Janet Fitch

·

The Ten-Year Nap by Meg Wolitzer

·

We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves by Karen Joy Fowler

·

Calling Invisible Women by Jeanne Ray (chick lit?)

·

In the Name of Friendship by Marilyn French

·

The House Girl by Tara Conklin*

·

Unless by

Carol Shields

|

Feminist

Fiction:

·

The Women’s Room by Marilyn French

·

In the Name of Friendship by Marilyn French

·

The Group by

Mary McCarthy

·

Top Girls (play)

by Caryl Churchill

·

The Shadow of the Sun by A. S. Byatt (?)

·

The Ten-Year Nap by Meg Wolitzer

·

Almost Famous Women by Megan Mayhew Bergman

·

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark

|

Prize-winning

Literature:

·

The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver

·

The Secret Life of Bees by Sue Monk Kidd

·

The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula Le Guin

·

How to be Both by Ali Smith

·

Outline by Rachel Cusk

·

The Red Tent by

Anita Diamant

·

Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout

·

The Invention of Wings by Sue Monk Kidd

·

Possession by

A. S. Byatt

·

A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley

·

Lavinia by Ursula

Le Guin

·

We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves by Karen Joy Fowler

·

The Nightingale by Kristin Hannah

·

Property by

Valerie Martin

·

Unless by

Carol Shields

|

Short

Story Collections:

·

The Unreal and the Real: Outer Space and Inner Lands by Ursula Le Guin:

-

“The Matter of

Seggri”

-

“Sur”

·

The Unreal and the Real: Where on Earth by Ursula Le Guin:

-

“Hand, Cup,

Shell”

·

Oliver Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout

·

Almost Famous Women by Megan Mayhew Bergman

|

Dystopian

+ Science Fiction:

·

The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula Le Guin

·

The Unreal and the Real: Where on Earth by Ursula Le Guin

·

The Unreal and the Real: Outer Space and Inner Lands by Ursula Le Guin:

·

The Gracekeepers by Kirsty Logan

·

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

|

||

Plays:

·

Top Girls (play)

by Caryl Churchill

·

Welcome to Thebes by Moira Buffini

|

The next round of selection will be concerned with identifying what ‘types’ of women’s stories are appropriate for the study of and deconstruction of women’s leadership. I imagine in this section I will investigate three key criteria for long listing suitable literature. These include, Badaracco’s test of ‘careful reading,’ the ‘Bechdel Test,’ and the presence of identifiable ‘moments’ of leadership within the narrative. Suitable women’s literature should move beyond the actions of a single, heroic leader figure, to encompass complex relationships between followers, purpose and context in the narrative.

From there I should easily be able to long-list 8-10 suitable titles, followed by a shortlist of 3-4 pieces of women's literature which work together to create a unified study on the issues facing female leaders. At the moment, the four interlinked themes I would like to work with include:

- The impact of gender on leadership (an exploration into social constructionism, gender & leadership)

- Reinterpreting the hierarchy - destabilising grand narratives

- Deconstructing popular stereotypes and expectations

- Leadership as process (women & post-heroic models of leadership)

I will leave it at that for now. The plan is to finish up the women & leadership section by mid-February, go on holiday for a week, come back and write-up the women's literature classification & selection by the beginning of March. #goals